After having spent more than five years in Romania, Ingo Tegge decided to collect all the weird, funny, and astonishing facts that he's learned about this country.

The Romanian language has a curious tendency

to adopt English compound nouns, then rip

them apart and use only a part of them to refer

to the whole. A “living” means living room, a

“parking” is a countable parking slot, and

“fresh” is Romanian for a freshly pressed juice.

This can get mildly confusing when the words

are re-introduced into English (which happens).

If an elderly person in Romania goes out of

their way to help you with something, there's a

traditional way of showing your appreciation:

gift them half a kilo of coffee. Sometimes, such

a “baksheesh” is even given before any help

is offered. Why coffee? It used to be a luxury

… and due to gentrification and sky-rocketing

costs of living, it might be one again, soon.

The 800,000 Romanian citizens in Germany

have adapted very well to their new home

to the point where they are virtually invisible.

Thus, they lack the political lobby and cultural

impact other immigrant groups have. A culinary

example: The Italians brought pizza, the Greeks

gyros, and Turks in Berlin invented the döner

kebab … but where are the sarmale bistros?

Romania is the country with the most religious

population (Special Eurobarometer 341) and

the largest diaspora relative to size (Eurostat)

in the European Union. Also, Romania has the

best broadband internet connection speed

(Speedtest.net). And Romania is the largest

exporter of pufuleti (to some 20 countries)

… but to be fair: it's also the only one.

Taxi drivers in Romania rarely wear seatbelts

which is completely legal. There's an urban

legend that the lawmakers considered it

unfair to force a part of the workforce to wear

seatbelts in their ‘office'. The real reason is that

seatbelts would make the drivers vulnerable to

attacks – which also means they can only go

seatbelt-free if they have a passenger.

1970s Romania criminalized social parasitism,

targeting ‘insolent youths'. However, a much

larger group of parasites came from North

America: Oak and sycamore (pictured) lace

bugs arrived in Europe a decade earlier. Now

their population explodes due to excessive

planting of host trees. A typical invasive alien

species (not the atypical extra-terrestrial kind).

In Romania, inviting an electrician, a plumber,

or any other specialist to your house always

results in the same ritual upon arrival: With an

offended, disbelieving look, they'll stare at the

item to be repaired and exclaim “Cine v-a lucrat

aici?!” (“Who worked here before?!”). To them,

all skilled craftspeople from Romania (besides

themselves) now live and work abroad.

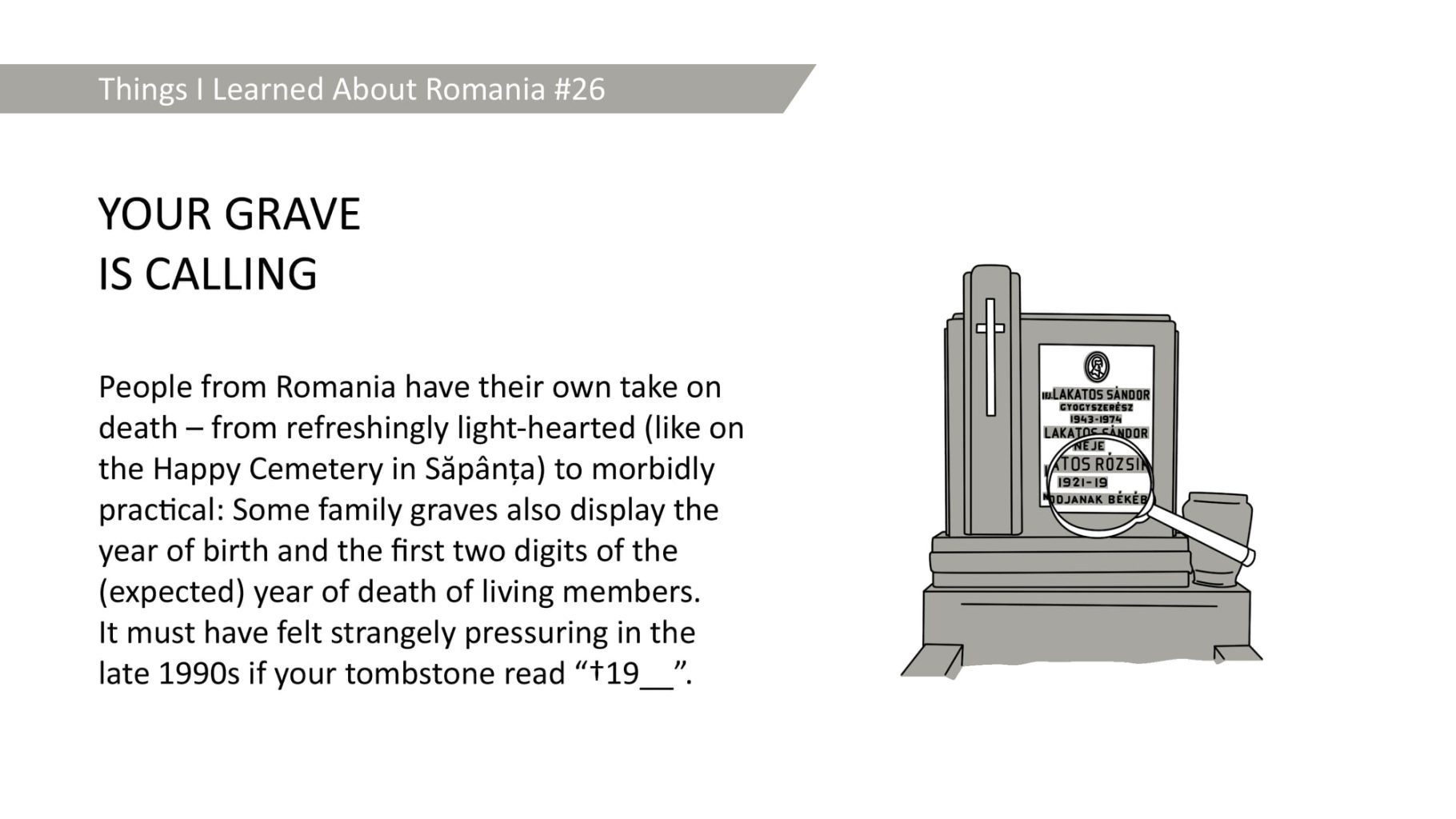

People from Romania have their own take on

death – from refreshingly light-hearted (like on

the Happy Cemetery in Sapânta) to morbidly

practical: Some family graves also display the

year of birth and the first two digits of the

(expected) year of death of living members.

It must have felt strangely pressuring in the

late 1990s if your tombstone read “+19__”.

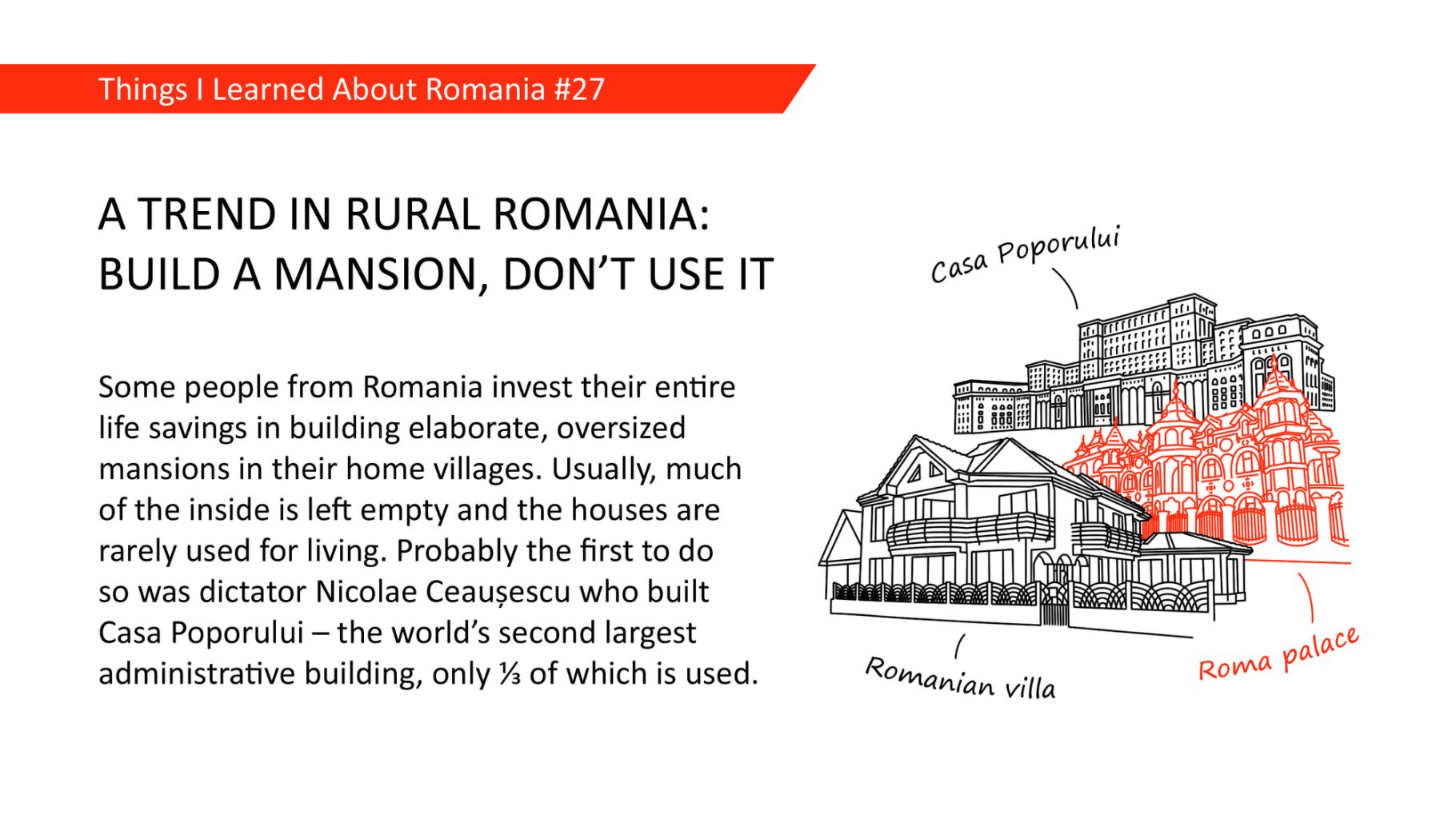

Some people from Romania invest their entire

life savings in building elaborate, oversized

mansions in their home villages. Usually, much

of the inside is left empty and the houses are

rarely used for living. Probably the first to do

so was dictator Nicola Ceausescu who built

Casa Poporului – the world's second largest

administrative building, only ⅓ of which is used.

In a country where political scandals are

plentiful, political leaders are replaced often,

and allegiances are quite fluid, what the

voters really want is something very mundane.

President Klaus lohannis' winning slogan for

the 2017 elections was the very understated

“Pentru o Românie normalà” (“For a normal

Romania”). The abbreviation was funny.

In Transylvania, young men splash women and

girls with lots of (presumably cold) spring water

on Easter Monday. This ritual is meant to “make

the girls grow”. Nowadays, the water shower is

often exchanged for sprays of perfume, resulting

in a chaotic mix of different smells. Worse: those

boys who cannot afford an exquisite perfume

often opt for a cheap deodorant instead.

![DEAD-PAN PRAGMATISM - The "impossible is not an option" work ethic is not very common in Romania - instead, people accept that some things just can't be done. This is epitomized in the expression "S-a rezolvat. Nu se poate." ("It's settled [resolved]. It's not possible."), which you might hear after discussing a difficult task. Typically accompanied by a shrug and expected to be as valid a result as any other.](https://clujxyz.com/media/clujbites/things-i-learned-about-romaia/things-i-learned-about-romania-30-1820x1024.jpeg)

The “impossible is not an option” work ethic is

not very common in Romania – instead, people

accept that some things just can't be done. This

is epitomized in the expression “S-a rezolvat.

Nu se poate.” (“It's settled [resolved]. It's not

possible.”), which you might hear after discussing

a difficult task. Typically accompanied by a shrug

and expected to be as valid a result as any other.

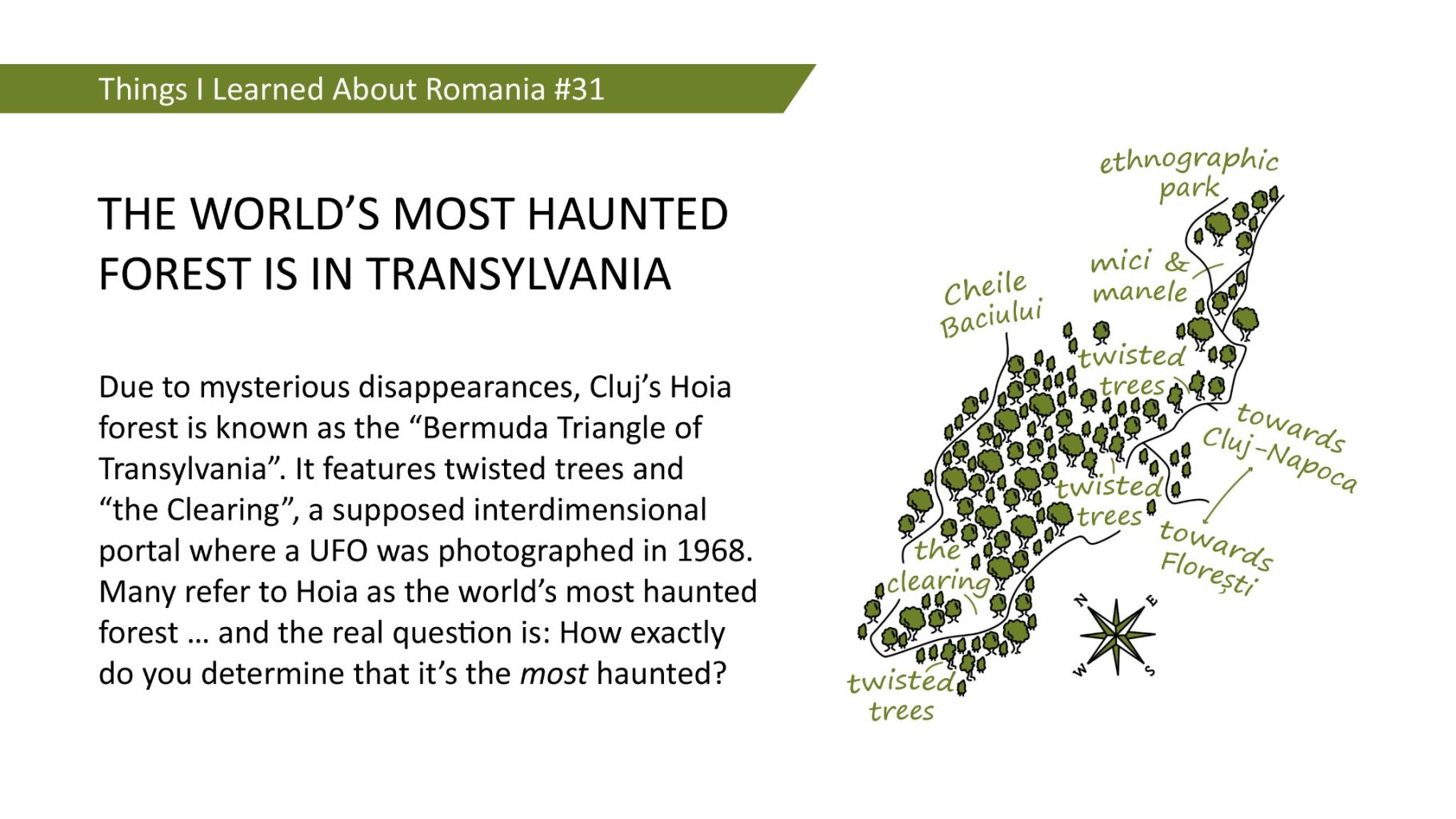

Due to mysterious disappearances, Cluj's Hoia

forest is known as the “Bermuda Triangle of

Transylvania”. It features twisted trees and

“the Clearing”, a supposed interdimensional

portal where a UFO was photographed in 1968.

Many refer to Hoia as the world's most haunted

forest … and the real question is: How exactly

do you determine that it's the most haunted?

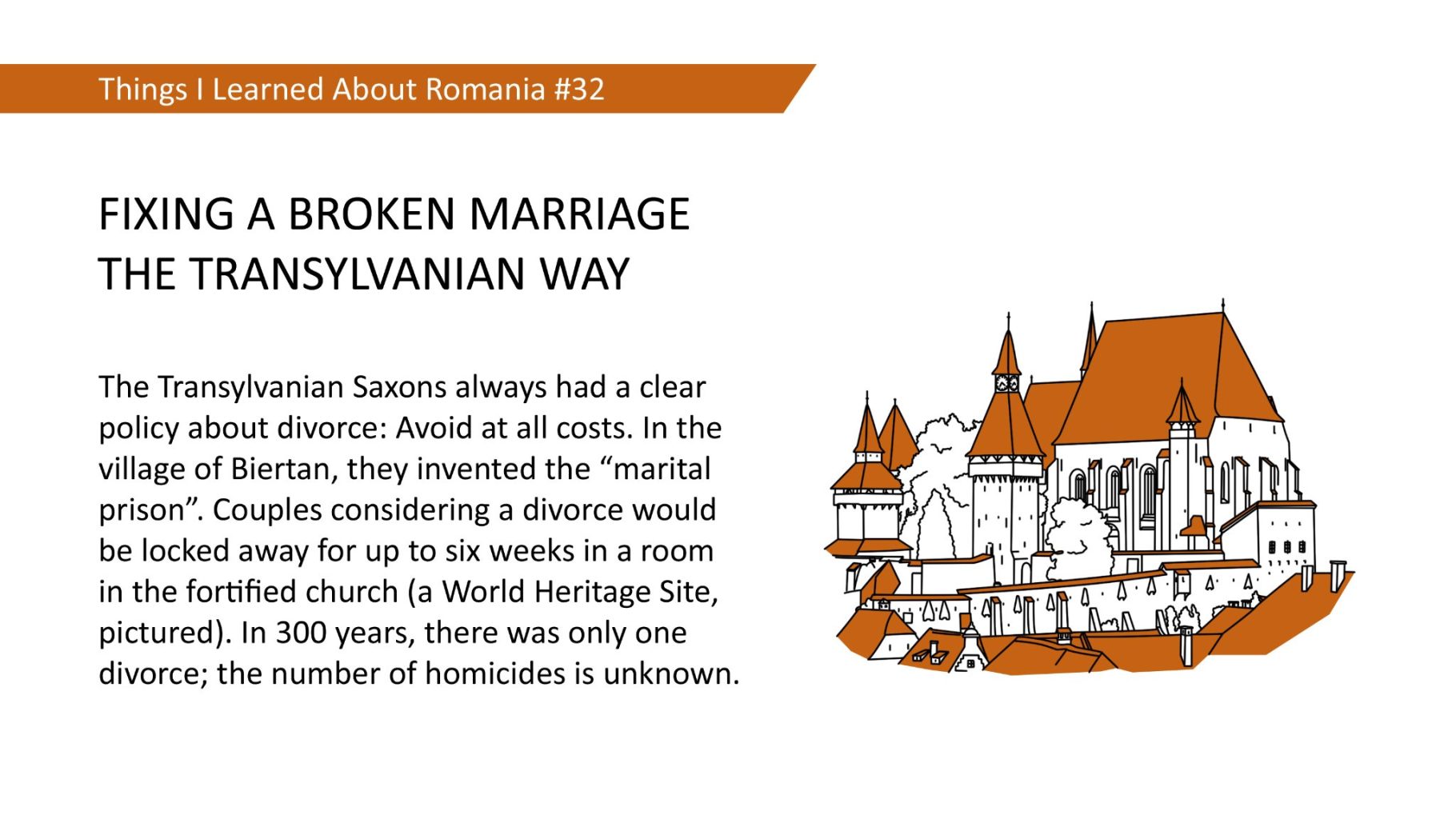

The Transylvanian Saxons always had a clear

policy about divorce: Avoid at all costs. In the

village of Biertan, they invented the “marital

prison”. Couples considering a divorce would

be locked away for up to six weeks in a room

in the fortified church (a World Heritage Site,

pictured). In 300 years, there was only one

divorce; the number of homicides is unknown.

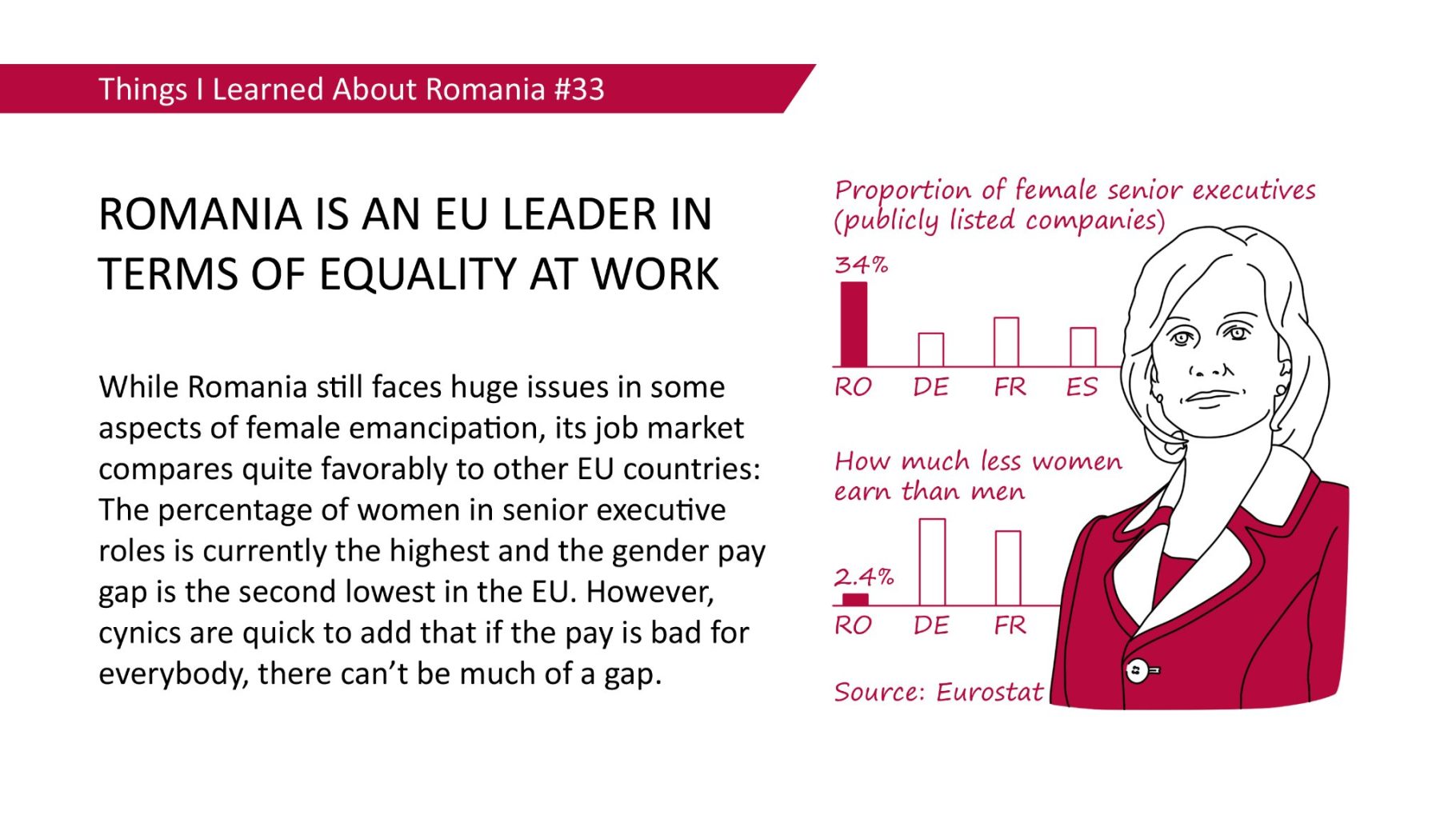

While Romania still faces huge issues in some

aspects of female emancipation, its job market

compares quite favorably to other EU countries:

The percentage of women in senior executive

roles is currently the highest and the gender pay

gap is the second lowest in the EU. However,

cynics are quick to add that if the pay is bad for

everybody, there can't be much of a gap.

Representing a high context culture, Romanian

does not focus on precision. Some examples:

“Ce faci?” means both “How are you?” and

“What are you doing?” and you say

“mami” to

your mother as well as your child. Also, famous

sculptor Constantin Brâncusi's “Endless Column'

isn't endless but 29.3m (to be fair, though: the

“Neverending Story” isn't never-ending, either).

Romania is home to the largest population of

bears in Europe after Russia. There's much

controversy on how many bears actually live in

the country and how to best deal with them

attacks on humans do happen. A good rule for

visitors: You don't have to be able to outrun a

bear (you won't anyway) – as long as you can

outrun at least one fellow tourist.

Bands of outlaws roamed Southeastern

Europe between the 17th and 19th centuries:

the haiduci. Similar to Robin Hood and his

Merry Men, their lives as highwaymen and

freedom fighters were later romanticized. In

reality, many haiduci focused more on the first

part of the whole “steal from the rich, give to

the poor” routine … but that's merely a detail.

Romanian weddings function as a community-

based loan system where the newlyweds get

huge cash presents – usually to buy a house –

in exchange for similar presents at the weddings

of their 300+ guests. The appropriate amount

depends on one's salary, the region, the day of

the week, and more. Popular website catdau.ro

(“How much to give”) helps with the calculation.

There are no vampires in Transylvania but you

can lose your blood further East: In the Danube

Delta – a vast, beautiful expanse of canals,

lakes, and wetlands (and a World Heritage Site).

You can find wild horses, protected fish and

rare bird species here … and mosquitoes. Lots

and lots of them. And if you're visiting during

the wrong season, they'll eat you alive.

Food is very important in Romanian culture

which explains why it's also the source of many

expressions in the Romanian language. To “take

someone out of their melons” (“1l scoti din

pepeni”) means to drive that person nuts. If

you're lying to someone, you're “selling donuts”

(“vinde gogosi”). And if you're exhausted, you

are “cabbage” (“varzä”). And so on …

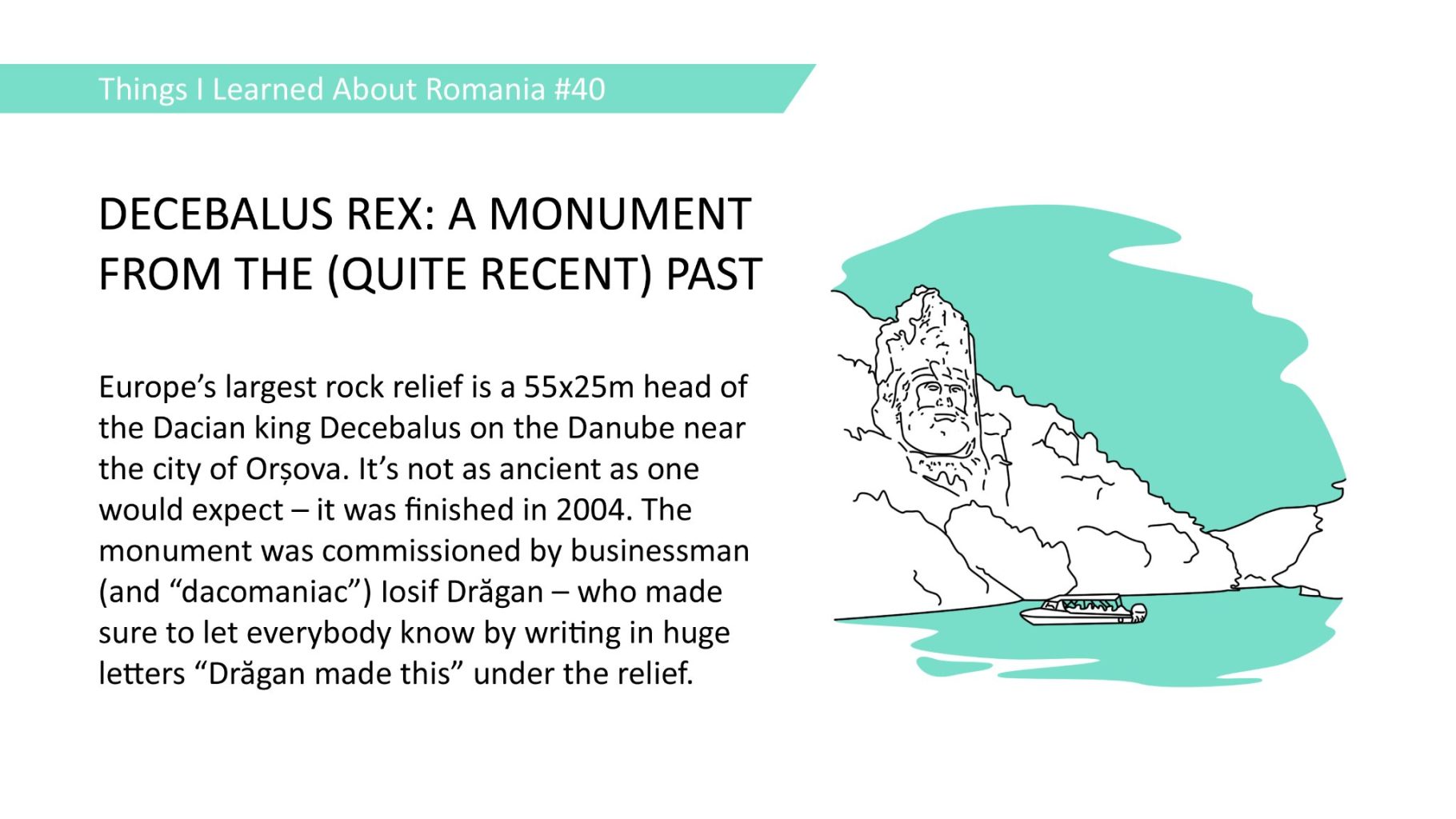

Europe's largest rock relief is a 55x25m head of

the Dacian king Decebalus on the Danube near

the city of Orsova. It's not as ancient as one

would expect – it was finished in 2004. The

monument was commissioned by businessman

(and “dacomaniac”) losif Drägan – who made

sure to let everybody know by writing in huge

letters “Drägan made this” under the relief.

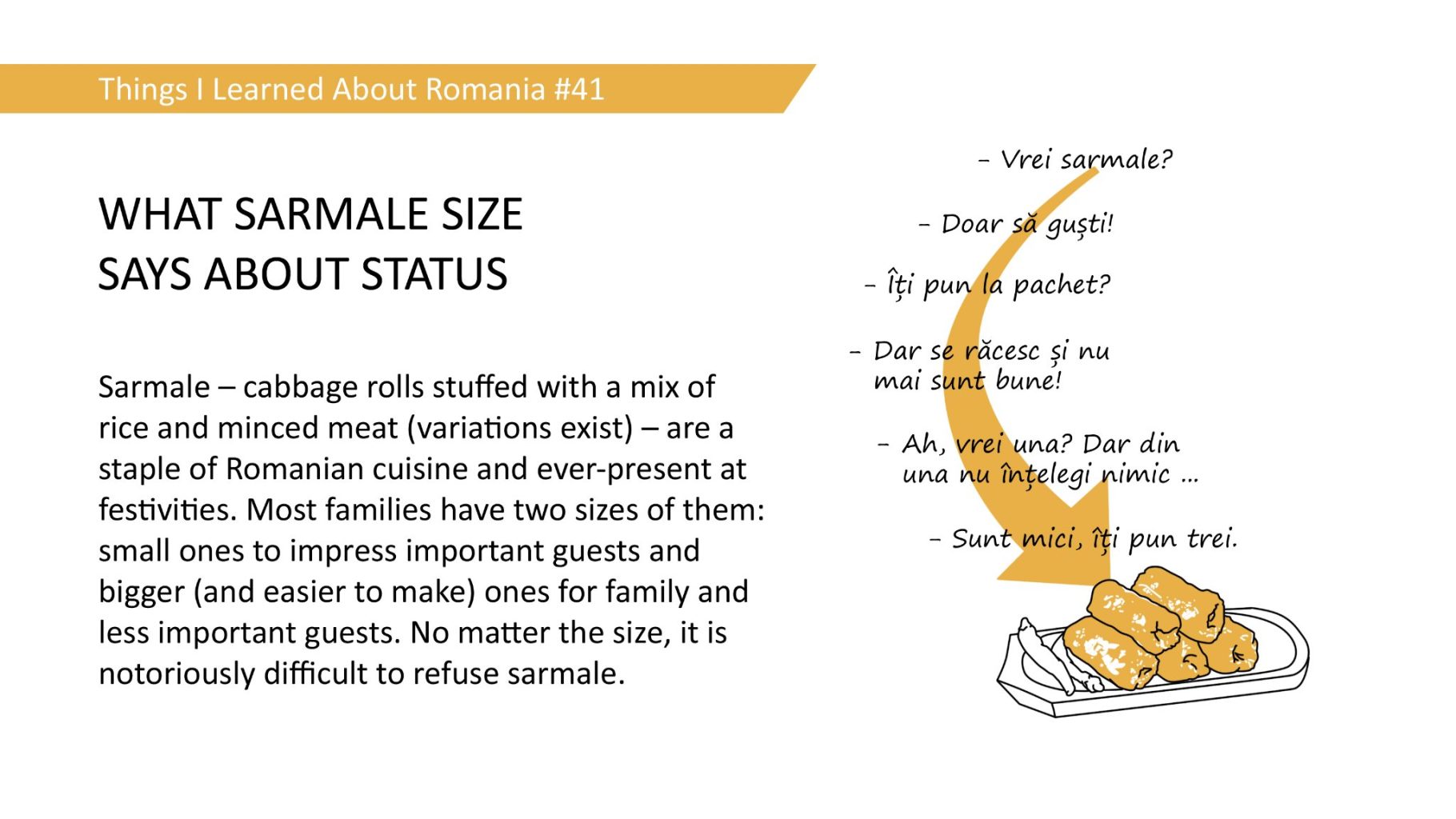

Sarmale – cabbage rolls stuffed with a mix of

rice and minced meat (variations exist) – are a

staple of Romanian cuisine and ever-present at

festivities. Most families have two sizes of them:

small ones to impress important guests and

bigger (and easier to make) ones for family and

less important guests. No matter the size, it is

notoriously difficult to refuse sarmale.

Irishman Bram Stoker intended to set his 1897

novel “Dracula” in the most remote, wild, and

ominous part of Europe he could think of

Inner Austria (Styria to be precise). Only when

his acquiantance Ármin Vámbéry, a Hungarian

orientalist, diplomat, and (alleged) secret agent,

told Stoker about Transylvania and Vlad Ill.

Dräculea, did he find his final setting and title.

View more of this series here.